Understanding by Design

| by Ryan S. Bowen | Print Version |

| Cite this guide: Bowen, R. S. (2017). Understanding by Design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/. |

- Overview

- The Benefits of Using Backward Design

- The Three Stages of Backward Design

- The Backward Design Template

Overview

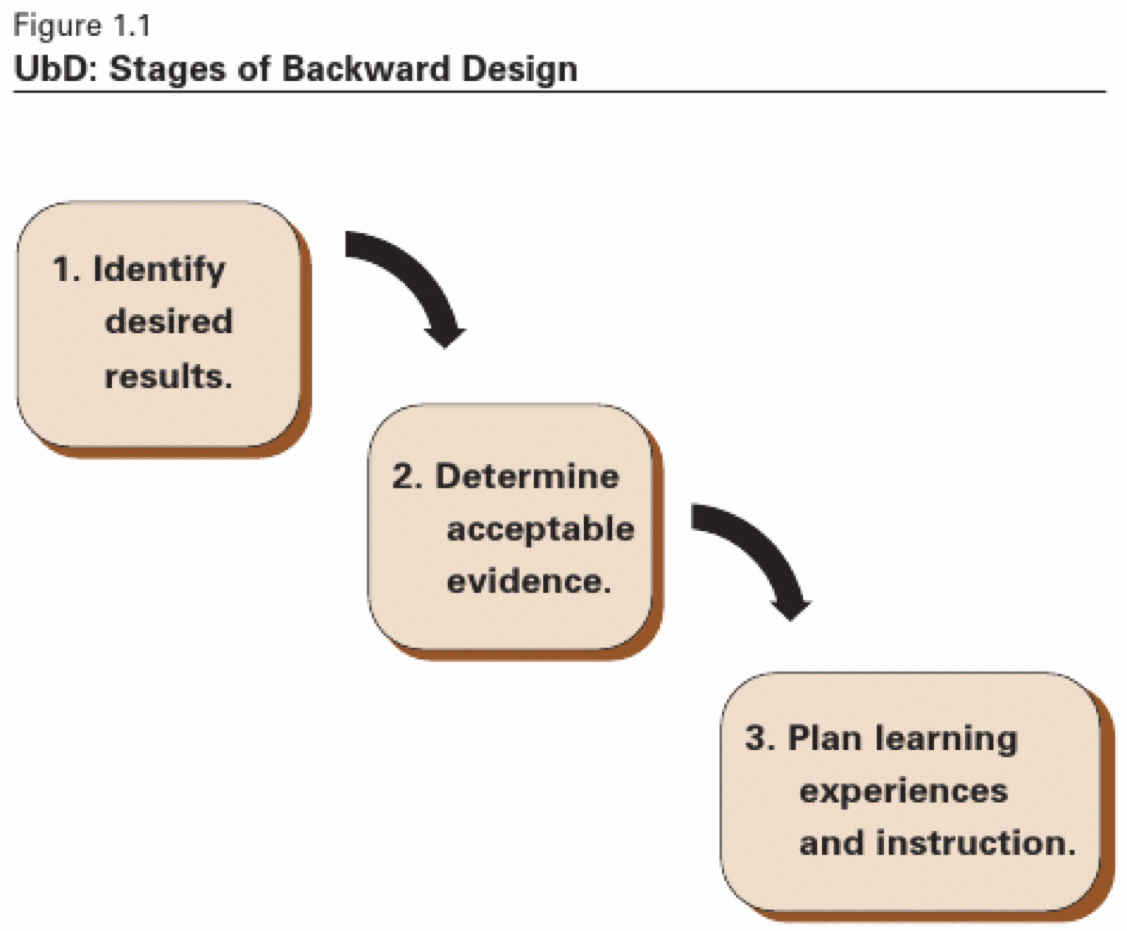

Understanding by Design is a book written by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe that offers a framework for designing courses and content units called “Backward Design.” Instructors typically approach course design in a “forward design” manner, meaning they consider the learning activities (how to teach the content), develop assessments around their learning activities, then attempt to draw connections to the learning goals of the course. In contrast, the backward design approach has instructors consider the learning goals of the course first. These learning goals embody the knowledge and skills instructors want their students to have learned when they leave the course. Once the learning goals have been established, the second stage involves consideration of assessment. The backward design framework suggests that instructors should consider these overarching learning goals and how students will be assessed prior to consideration of how to teach the content. For this reason, backward design is considered a much more intentional approach to course design than traditional methods of design.

This teaching guide will explain the benefits of incorporating backward design. Then it will elaborate on the three stages that backward design encompasses. Finally, an overview of a backward design template is provided with links to blank template pages for convenience.

The Benefits of Using Backward Design

“Our lessons, units, and courses should be logically inferred from the results sought, not derived from the methods, books, and activities with which we are most comfortable. Curriculum should lay out the most effective ways of achieving specific results… in short, the best designs derive backward from the learnings sought.”

In Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe argue that backward design is focused primarily on student learning and understanding. When teachers are designing lessons, units, or courses, they often focus on the activities and instruction rather than the outputs of the instruction. Therefore, it can be stated that teachers often focus more on teaching rather than learning. This perspective can lead to the misconception that learning is the activity when, in fact, learning is derived from a careful consideration of the meaning of the activity.

As previously stated, backward design is beneficial to instructors because it innately encourages intentionality during the design process. It continually encourages the instructor to establish the purpose of doing something before implementing it into the curriculum. Therefore, backward design is an effective way of providing guidance for instruction and designing lessons, units, and courses. Once the learning goals, or desired results, have been identified, instructors will have an easier time developing assessments and instruction around grounded learning outcomes.

The incorporation of backward design also lends itself to transparent and explicit instruction. If the teacher has explicitly defined the learning goals of the course, then they have a better idea of what they want the students to get out of learning activities. Furthermore, if done thoroughly, it eliminates the possibility of doing certain activities and tasks for the sake of doing them. Every task and piece of instruction has a purpose that fits in with the overarching goals and goals of the course.

As the quote below highlights, teaching is not just about engaging students in content. It is also about ensuring students have the resources necessary to understand. Student learning and understanding can be gauged more accurately through a backward design approach since it leverages what students will need to know and understand during the design process in order to progress.

“In teaching students for understanding, we must grasp the key idea that we are coaches of their ability to play the ‘game’ of performing with understanding, not tellers of our understanding to them on the sidelines.”

The Three Stages of Backward Design

“Deliberate and focused instructional design requires us as teachers and curriculum writers to make an important shift in our thinking about the nature of our job. The shift involves thinking a great deal, first, about the specific learnings sought, and the evidence of such learnings, before thinking about what we, as the teacher, will do or provide in teaching and learning activities.”

Stage One

Stage Two

Stage Three

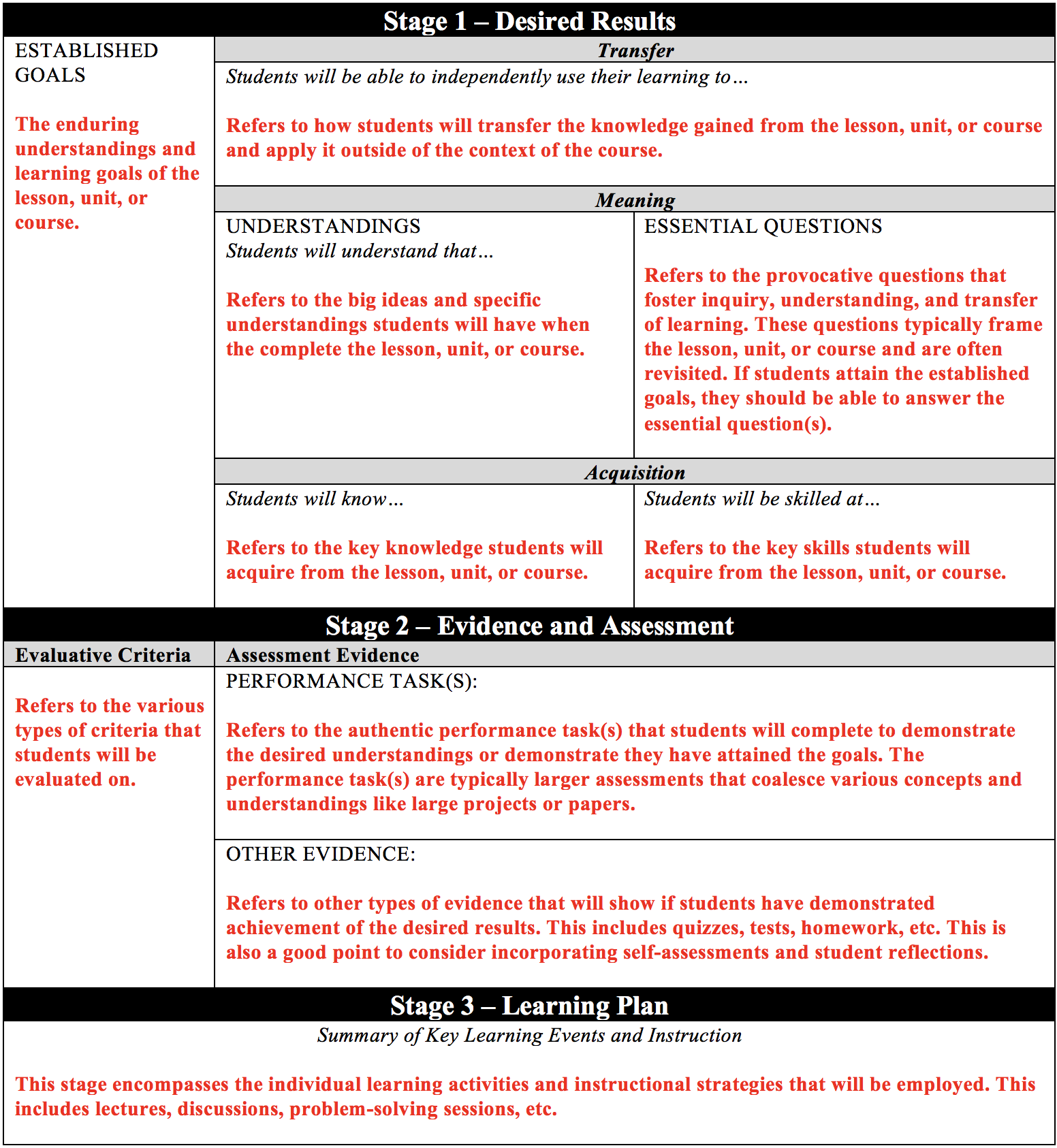

The Backward Design Template

A link to the blank backward design template is provided here (https://jaymctighe.com/resources/), and it is referred to as UbD Template 2.0. The older version (version 1.0) can also be downloaded at that site as well as other resources relevant to Understanding by Design. The template walks individuals through the stages of backward design. However, if you are need of the template with descriptions of each section, please see the table below. There is also a link to the document containing the template with descriptions provided below and can be downloaded for free.

Backward Design Template with Descriptions (click link for template with descriptions).